Every Python developer is challenged by the size and velocity of the Python ecosystem 😤

This post provides clarity with a Hypermodern Python Toolbox - tools that are setting the standard for Python in 2025.

Python 3.11 and 3.12 have both brought performance improvements to Python. We choose 3.11 as 3.12 is still a bit unstable with some popular data science libraries.

So much of programming is reading & responding error messages - error message improvements are a great quality of life improvement for Python developers in 2025.

Python 3.11 added better tracebacks - the exact location of the error is pointed out in the traceback. This improves the information available to you during development and debugging.

The code below has a mistake. We want to assign a value to the first element of data, but the code refers to a non-existent variable datas:

data = [1, 4, 8]

# the variable datas does not exist!

datas[0] = 2With pre 3.10 versions of Python, this results in an error traceback that points out that the variable datas doesn’t exist:

$ uv run --python 3.9 --no-project mistake.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/Users/adamgreen/data-science-south-neu/mistake.py", line 3, in <module>

datas[0] = 2

NameError: name 'datas' is not defined

Python 3.11 takes its diagnosis two steps further and also offers a solution that the variable should be called data instead, and points out where on the line the error occurred:

$ uv run --python 3.11 --no-project mistake.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/Users/adamgreen/data-science-south-neu/mistake.py", line 3, in <module>

datas[0] = 2

^^^^^

NameError: name 'datas' is not defined. Did you mean: 'data'?

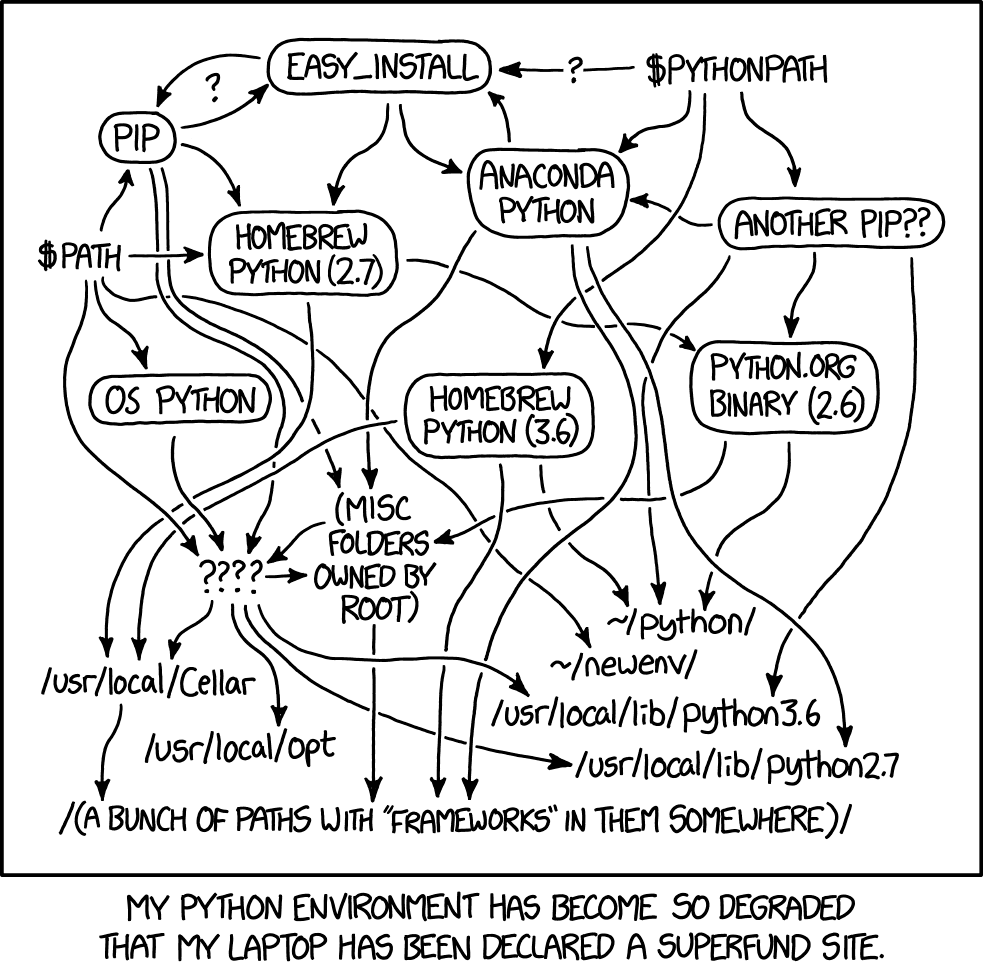

The hardest thing about learning Python is learning to install & manage Python. Even senior developers can struggle with the complexity of managing Python, especially if it is not their main language.

uv is a tool for managing different versions of Python. It’s an alternative to using pyenv, miniconda or installing Python from a downloaded installer.

uv can be used to run Python commands and scripts with the Python version specified - uv will download the Python version if it needs to. This massively simplifies the complexity of managing different versions of Python locally.

The command below runs a hello world program with Python 3.12:

$ uv run --python 3.12 --no-project python -c "print('hello world')"

hello

uv is also a tool for managing virtual environments in Python. It’s an alternative to venv or miniconda. Virtual environments allow separate installations of Python to live side-by-side, which makes working on different projects possible locally.

The command below creates a virtual environment with Python 3.11:

$ uv venv --python 3.11

Using CPython 3.11.10

Creating virtual environment at: .venv

Activate with: source .venv/bin/activate

You will need to activate the virtual environment to use it with $ source activate .venv/bin.

uv is also a tool for managing Python dependencies and packages. It’s an alternative to pip. Pip, Poetry and uv can all be used to install and upgrade Python packages.

Below is an example pyproject.toml for a uv managed project:

[project]

name = "hypermodern"

version = "0.0.1"

requires-python = ">=3.11,<3.12"

dependencies = [

"pandas>=2.0.0",

"requests>=2.31.0"

]

[project.optional-dependencies]

test = ["pytest>=7.0.0"]Installing a project can be done by pointing uv pip install at our pyproject.toml:

$ uv pip install -r pyproject.toml

Resolved 11 packages in 1.69s

Installed 11 packages in 61ms

+ certifi==2024.12.14

+ charset-normalizer==3.4.0

+ idna==3.10

+ numpy==2.2.0

+ pandas==2.2.3

+ python-dateutil==2.9.0.post0

+ pytz==2024.2

+ requests==2.32.3

+ six==1.17.0

+ tzdata==2024.2

+ urllib3==2.2.3

Like Poetry, uv can lock the dependencies into uv.lock:

$ uv lock

Resolved 17 packages in 5ms

uv can also be used to add tools, which are globally available Python tools. The command below installs pytest as tool we can use anywhere:

$ uv tool install --python 3.11 pytest

Resolved 4 packages in 525ms

Installed 4 packages in 7ms

+ iniconfig==2.0.0

+ packaging==24.2

+ pluggy==1.5.0

+ pytest==8.3.4

Installed 2 executables: py.test, pytest

This will add programs that are available outside of a virtual environment:

$ which pytest

/Users/adamgreen/.local/bin/pytest

Tip - add the direnv tool with a .envrc to automatically switch to the correct Python version when you enter a directory.

Ruff is a tool to lint and format Python code - it is an alternatives to tools like Black or autopep8.

Ruff’s big thing is being written in Rust - this makes it fast. Ruff covers much of the Flake8 rule set, along with other rules such as isort.

The code below has three problems:

datas.data = datas[0]

import collectionsRunning Ruff in the same directory points out the issues:

$ ruff check .

ruff.py:1:8: F821 Undefined name `datas`

ruff.py:2:1: E402 Module level import not at top of file

ruff.py:2:8: F401 [*] `collections` imported but unused

Found 3 errors.

[*] 1 potentially fixable with the --fix option.

Tip - Ruff is quick enough to run on file save during development - make sure you have formatting on save configured in your text editor!

mypy is a tool for enforcing type safety in Python - it’s an alternative to limiting type declarations to unexecuted documentation.

Recently Python has undergone a similar transition to the Javascript to Typescript transition, with static typing becoming core to Python development (if you want). Statically typed Python is the standard for many teams developing Python in 2025.

Static type checking will catch some bugs that many unit test suites won’t. Static typing will check more paths than a single unit test often does - catching edge cases that would otherwise only occur in production.

mypy_error.py has a problem - we attempt to divide a string by 10:

def process(user):

# line below causes an error

user['name'] / 10

user = {'name': 'alpha'}

process(user)We can catch this error by running mypy - catching the error without actually executing the Python code:

$ mypy --strict mypy_error.py

mypy_error.py:1: error: Function is missing a type annotation

mypy_error.py:5: error: Call to untyped function "process" in typed context

Found 2 errors in 1 file (checked 1 source file)

These first errors are because our code has no typing - we can add two type annotations to make our code typed:

user: dict[str,str] - user is a dictionary with strings as keys and values,-> None: - the process function returns None.def process(user: dict[str,str]) -> None:

user['name'] / 10

user = {'name': 'alpha'}

process(user)Running mypy on mypy_intermediate.py, mypy points out the error in our code:

$ mypy --strict mypy_intermediate.py

mypy_fixed.py:2: error: Unsupported operand types for / ("str" and "int")

Found 1 error in 1 file (checked 1 source file)

This is a test we can run without writing any specific test logic - very cool!

Tip - Use reveal_type(variable) in your code when debugging type issues. mypy will show you what type it thinks a variable has.

Pydantic is a tool for organizing and validating data in Python - it’s an alternative to using dictionaries or dataclasses.

Pydantic is part of Python’s typing revolution - Pydantic’s ability to create and validate custom types makes your Python code clearer and safer.

Pydantic uses Python type hints to define data types. Imagine we want a user with a name and id, which we could model with a dictionary:

import uuid

users = [

{'name': 'alpha', 'id': str(uuid.uuid4())},

{'name': 'beta'},

{'name': 'omega', 'id': 'invalid'}

]We could also model this with Pydantic - introducing a class that inherits from pydantic.BaseModel:

import uuid

import pydantic

class User(pydantic.BaseModel):

name: str

id: str = None

users = [

User(name='alpha', 'id'= str(uuid.uuid4())),

User(name='beta'),

User(name='omega', id='invalid'),

]A strength of Pydantic is validation - we can introduce some validation of our user ids - below checking that the id is a valid GUID - otherwise setting to None:

import uuid

import pydantic

class User(pydantic.BaseModel):

name: str

id: str = None

@pydantic.validator('id')

def validate_id(cls, user_id:str ) -> str | None:

try:

user_id = uuid.UUID(user_id, version=4)

print(f"{user_id} is valid")

return user_id

except ValueError:

print(f"{user_id} is invalid")

return None

users = [

User(name='alpha', id= str(uuid.uuid4())),

User(name='beta'),

User(name='omega', id='invalid'),

]

[print(user) for user in users]Running the code above, our Pydantic model has rejected one of our ids - our omega has had it’s original ID of invalid rejected and ends up with an id=None:

$ python pydantic_eg.py

45f3c126-1f50-48bf-933f-cfb268dca39a is valid

invalid is invalid

name='alpha' id=UUID('45f3c126-1f50-48bf-933f-cfb268dca39a')

name='beta' id=None

name='omega' id=None

These Pydantic types can become the primitive data structures in your Python programs (instead of dictionaries) - making it eaiser for other developers to understand what is going on.

Tip - you can generate Typescript types from Pydantic models - making it possible to share the same data structures with your Typescript frontend and Python backend.

Typer is a tool for building command line interfaces (CLIs) using type hints in Python - it’s an alternative to sys.argv or argparse.

We can build a Python CLI with uv and Typer by first creating a Python package with uv, adding typer as a dependency).

First create a virtual environment:

$ uv venv --python=3.11.10

Using CPython 3.11.10

Creating virtual environment at: .venv

Activate with: source .venv/bin/activate

Then use uv init to create a new project from scratch:

$ uv init --name demo --python 3.11.10 --package

Initialized project `demo`

This creates a project:

$ tree

.

├── pyproject.toml

├── README.md

└── src

└── demo

└── __init__.py

We can then add typer as a dependency with uv add:

$ uv add typer

Using CPython 3.11.10

Creating virtual environment at: .venv

Resolved 10 packages in 2ms

Installed 8 packages in 9ms

+ click==8.1.8

+ markdown-it-py==3.0.0

+ mdurl==0.1.2

+ pygments==2.18.0

+ rich==13.9.4

+ shellingham==1.5.4

+ typer==0.15.1

+ typing-extensions==4.12.2

We then add modify the Python file src/demo/__init__.py to include a simple CLI:

import typer

app = typer.Typer()

@app.command()

def main(name: str) -> None:

print(f"Hello {name}")We need to add this to our pyproject.toml to be able to run our CLI with the demo command:

demo = "demo:app"This is our full pyproject.toml:

[project]

name = "demo"

version = "0.1.0"

description = "Add your description here"

readme = "README.md"

authors = [

{ name = "Adam Green", email = "adam.green@adgefficiency.com" }

]

requires-python = ">=3.11.10"

dependencies = [

"typer>=0.15.1",

]

[project.scripts]

demo = "demo:app"

[build-system]

requires = ["hatchling"]

build-backend = "hatchling.build"Because we have included a [project.scripts] in our pyproject.toml, we can run this CLI with uv run:

$ uv run demo omega

Hello omega

Typer gives us a --help flag for free:

$ python src/demo/__init__.py --help

Usage: demo [OPTIONS] NAME

╭─ Arguments ──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╮

│ * name TEXT [default: None] [required] │

╰──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯

╭─ Options ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╮

│ --install-completion Install completion for the current shell. │

│ --show-completion Show completion for the current shell, to copy it or customize │

│ the installation. │

│ --help Show this message and exit. │

╰──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯

Tip - you can create nested CLI groups in typer using commands and command groups.

Rich is a tool for printing pretty text to a terminal - it’s an alternative to the monotone terminal output of most Python programs.

Rich’s features pretty printing of color and emojis:

import rich

user = {'name': 'omega', 'id': 'invalid'}

print(f" normal printing\nuser {user}\n")

rich.print(f" :wave: rich printing\nuser {user}\n") normal printing

user {'name': 'omega', 'id': 'invalid'}

👋 rich printing

user {'name': 'omega', 'id': 'invalid'}If you are happy with Rich you can simplify your code by replacing the built-in print with the Rich print:

from rich import print

print('this will be printed with rich :clap:')this will be printed with rich 👏Tip - Rich offers much more than color and emojis - including displaying tabular data and better trackbacks of Python errors.

Polars is a tool for tabular data manipulation in Python - it’s an alternative to Pandas or Spark.

Polars offers query optimization, parallel processing and can work with larger than memory datasets. It also has a syntax that many prefer to Pandas.

Query optimization allows multiple data transformations to be grouped together and optimized over. This cannot be done in eager-execution frameworks like Pandas, each data transformation is run without knowledge of what came before and after.

Let’s start with a dataset with three columns:

import polars as pl

df = pl.DataFrame({

'date': ['2025-01-01', '2025-01-02', '2025-01-03'],

'sales': [1000, 1200, 950],

'region': ['North', 'South', 'North']

})Below we chain together column creation and aggregation into one query:

query = (

df

# start lazy evaluation - Polars won't execute anything until .collect()

.lazy()

# with_columns adds new columns

.with_columns(

[

# parse string to date

pl.col("date").str.strptime(pl.Date).alias("date"),

# add a new column with running total

pl.col("sales").cum_sum().alias("cumulative_sales"),

]

)

# column to group by

.group_by("region")

# how to aggregate the groups

.agg(

[

pl.col("sales").mean().alias("avg_sales"),

pl.col("sales").count().alias("n_days"),

]

)

)

# run the optimized query

print(query.collect())shape: (2, 3)

┌────────┬───────────┬────────┐

│ region ┆ avg_sales ┆ n_days │

│ --- ┆ --- ┆ --- │

│ str ┆ f64 ┆ u32 │

╞════════╪═══════════╪════════╡

│ North ┆ 975.0 ┆ 2 │

│ South ┆ 1200.0 ┆ 1 │

└────────┴───────────┴────────┘We can use Polars to explain our query:

print(query.explain())AGGREGATE

[col("sales").mean().alias("avg_sales"), col("sales").count().alias("n_days")] BY [col("region")] FROM

DF ["date", "sales", "region"]; PROJECT 2/3 COLUMNS; SELECTION: NonTip - you can use pl.DataFrame.to_pandas() to convert a Polars DataFrame to a Pandas DataFrame. This can be useful to slowly refactor a Pandas based pipeline into a Polars based pipeline.

Pandera is a tool for data quality checks of tabular data - it’s an alternative to Great Expectations or assert statements.

Pandera allows you to define schemas for tabular data (data with rows and columns), which are used validate a table of data. By defining schemas explicitly, Pandera can catch data issues before they propagate through your analysis pipeline.

Below we create a schema for sales data, including a few data quality checks:

import polars as pl

import pandera as pa

from pandera.polars import DataFrameSchema, Column

schema = DataFrameSchema(

{

"date": Column(

pa.DateTime,

nullable=False,

coerce=True,

title="Date of sale"

),

"sales": Column(

int,

checks=[pa.Check.greater_than(0), pa.Check.less_than(10000)],

title="Daily sales amount",

),

"region": Column(

str,

checks=[pa.Check.isin(["North", "South", "East", "West"])],

title="Sales region",

),

}

)We can now validate data using this schema:

data = pl.DataFrame({

"date": ["2025-01-01", "2025-01-02", "2025-01-03"],

"sales": [1000, 1200, 950],

"region": ["North", "South", "East"]

})

data = data.with_columns(pl.col("date").str.strptime(pl.Date, "%Y-%m-%d"))

print(schema(data))shape: (3, 3)

┌────────────┬────────┬────────┐

│ date ┆ sales ┆ region │

│ --- ┆ --- ┆ --- │

│ datetime ┆ f64 ┆ str │

╞════════════╪════════╪════════╡

│ 2025-01-01 ┆ 1000.0 ┆ North │

│ 2025-01-02 ┆ 1200.0 ┆ South │

│ 2025-01-03 ┆ 950.0 ┆ North │

└────────────┴────────┴────────┘When we have bad data, Pandera will raise an exception:

data = pl.DataFrame({

"date": ["2025-01-01", "2025-01-02", "2025-01-03"],

"sales": [-1000, 1200, 950],

"region": ["North", "South", "East"]

})

data = data.with_columns(pl.col("date").str.strptime(pl.Date, "%Y-%m-%d"))

print(schema(data))SchemaError: Column 'sales' failed validator number 0: <Check greater_than: greater_than(0)> failure case examples: [{'sales': -1000}]Tip - Pandera also offers a Pydantic style class based API that can validate using Python types.

DuckDB is database for analytical SQL queries - it’s an alternative to SQLite, Polars, Spark and Pandas.

DuckDB is a single-file database like SQLite. While SQLite is optimized for row based, transactional workloads, DuckDB is designed for column based, analytical queries. DuckDB shines when working with larger than memory datasets. It can efficiently query Parquet files directly without loading them into memory first.

Let’s create some sample data using both CSV and Parquet formats:

import duckdb

import polars as pl

sales = pl.DataFrame(

{

"date": ["2025-01-01", "2025-01-02", "2025-01-03"],

"product_id": [1, 2, 1],

"amount": [100, 150, 200],

}

).to_csv("sales.csv", index=False)

products = pl.DataFrame(

{"product_id": [1, 2], "name": ["Widget", "Gadget"], "category": ["A", "B"]}

).to_parquet("products.parquet")Below we run a SQL query across both data formats:

con = duckdb.connect()

print(

con.execute(

"""

WITH daily_sales AS (

SELECT

date,

product_id,

SUM(amount) as daily_total

FROM 'sales.csv'

GROUP BY date, product_id

)

SELECT

s.date,

p.name as product_name,

p.category,

s.daily_total

FROM daily_sales s

JOIN 'products.parquet' p ON s.product_id = p.product_id

ORDER BY s.date, p.name

"""

).df()

) date product_name category daily_total

0 2025-01-01 Widget A 100

1 2025-01-02 Gadget B 150

2 2025-01-03 Widget A 200Tip - Use DuckDB’s EXPLAIN command to understand query execution plans and optimize your queries.

Loguru is a logger - it’s an alternative to the standard library’s logging module and structlog.

Loguru builds on top of the Python standard library logging module. It’s not a complete rethinking, but a few tweaks that make logging from Python programs less painful. Because Loguru builds on top of the Python logging module, it’s easy to swap in a Loguru logger for a Python standard library logging.Logger.

A central Loguru idea is that there is only one logger. This is a great example of the unintuitive value of constraints - having less logger objects is actually better than being able to create many.

Logging with Loguru is as simple as from loguru import logger:

from loguru import logger

logger.info("Hello, Loguru!")2025-01-04 02:28:37.622 | INFO | __main__:<module>:3 - Hello, Loguru!Configuring the logger is all done through a single logger.add call.

We can configure how we log to std.out:

logger.add(

sys.stdout,

colorize=True,

format="<green>{time}</green> <level>{message}</level>",

level="INFO"

)The code below configures logging to a file:

logger.add(

"log.txt",

format="{time} {level} {message}",

level="DEBUG"

)Tip - Loguru supports structured logging of records to JSON via the logger.add("log.txt", seralize=True) argument.

Marimo is a Python notebook editor and format - it’s an alternative to Jupyter Lab and the JSON Jupyter notebook file format.

Marimo offers multiple improvements over older ways of writing Python notebooks:

Marimo also offers the feature of being reactive - cells can be re-executed when their inputs change. This can be a double-edged sword for some notebooks, where changing a call can cause side effects like querying APIs or databases.

Marimo notebooks are stored as pure Python files, which means that:Git diffs are meaningful, and the notebook can be executed as a script.

Below is an example of the Marimo notebook format:

import marimo

__generated_with = "0.10.12"

app = marimo.App(width="medium")

@app.cell

def _():

import pandas as pd

def func():

return None

print("hello")

return func, pd

if __name__ == "__main__":

app.run()Tip - Marimo integrates with GitHub Copilot and Ruff code formatting.

The 2025 Hypermodern Python Toolbox is: