Git is a version control system that allows developers to track changes in text files.

Minimal Git workflow - the four shell commands are the core of a daily Git workflow:

$ git status

$ git add -u OR git add path/to/file

$ git commit -m 'message'

$ git push

Create and commit to a local repository:

$ git init

$ git add README.md # add specific file

$ git add . # add all files in current directory

$ git add -u # add all tracked files that have been modified

$ git commit -m "chore: initial commit"

$ git push

Clone and push to a remote repository:

$ git clone https://github.com/username/repo.git # HTTPS

$ git clone git@github.com:username/repo.git # SSH

$ cd repo

$ git add README.md

$ git commit -m "docs: update readme"

$ git push

Create a repository from scratch and connect to the origin remote repository:

$ git init

$ git add README.md

$ git commit -m "initial commit"

$ git remote add origin https://github.com/username/repo.git

$ git push -u origin main

Create, switch and track branches:

$ git branch # list all branches

$ git branch feature-branch # create new branch

$ git checkout feature-branch # switch to branch

$ git checkout -b feature-branch # create and switch to branch

$ git checkout main # switch back to `main` branch

$ git checkout -b local-branch origin/remote-branch # create local branch tracking remote

git init, connecting to remote repositories, and understanding the .git directory structuregit add to stage changes and git commit to create snapshots of your codebase with descriptive messagesgit status, git add, git commit, and git push for daily development workgit branch and git checkout to work on features without affecting the main codebaseRecommended resources to learn Git:

Because Git is popular, LLM tools like Claude are excellent learning and development partners for Git.

Git is a popular version control tool - many of the tools you use Git as the core version control engine. An example is GitHub, which builds on top of Git, and is where many developers keep their code.

Learning Git will allow you to do:

Git enables managing software through a Software Development Lifecycle (SDLC).

It enables moving code between environments in a safe and repeatable way. As code is merged into specific branches (like dev or prod), side effects like running tests or deploying to the cloud can occur.

An example of how code is branched to manage deployments across two environments (dev and prod) is below:

Most modern software development teams use multiple environments to safely develop, test, and deploy code. Common environments include:

You may also come across environments called test, pre-prod, quality assurance (QA), or user acceptance testing (UAT).

It’s also possible for individual developers to have their own environments - a completely separate set of cloud infrastructure that is deployed from feature branches they are working on. This allows developers to change their entire stack during development, without affecting anyone else on the cloud. Developer environments do require a reasonable level of technical sophistication to set up and maintain, so are not common.

Which environments you need depends on the work you are doing, how many other people are doing development on the same code and company culture.

Git facilitates a SDLC by:

Different developers use different tools for using Git.

This lesson focuses on using Git through a terminal via a CLI. This is because if we can use Git via a CLI, we can use it both interactively as we work and in CI/CD pipelines.

Other Git tools include:

Git commits & branches can be naturally visualized, making visual tools popular and useful.

On Windows, Git Bash is a great way to access Git - you can use start . to open a folder in Windows Explorer.

There are three main methods of authentication with Git.

When working with remote repositories, you’ll need to authenticate with the Git server. Authentication can be the hardest part about development sometimes - knowing which method to use, or getting one method to work.

Git Credential Manager (GCM) is a secure and user-friendly way to store your authentication credentials for Git repositories.

Install GCM on Ubuntu Linux (no need on Windows and MacOS):

$ sudo apt install git-credential-manager

Configure Git to use the credential manager:

$ git config --global credential.helper manager

When you first clone or push to a remote repository, GCM will prompt you to authenticate and then securely store your credentials.

SSH (Secure Shell) keys are a secure way to authenticate with Git servers without entering your password each time.

$ ssh-keygen -t ed25519 -C "your_email@example.com"

~/.ssh/id_ed25519.pub.$ git clone git@github.com:username/repo.git

SSH keys are more secure than passwords and don’t expire, making them ideal for development machines.

Personal Access Tokens are an alternative to passwords when authenticating with Git servers.

PATs are useful for:

For security, treat PATs like passwords and avoid committing them to your repositories.

Often PAT are set as environment variables, like OPENAI_API_KEY, which any program run can access.

Git naturally lends itself to visualization - many developers prefer to use a graphical user interface (GUI) to interact with Git.

You can find a list of Git GUI tools here.

It’s also possible to use Git only via a command line interface (CLI).

Install Git here - you can then use the Git CLI:

$ git --help

usage: git [-v | --version] [-h | --help] [-C <path>] [-c <name>=<value>]

[--exec-path[=<path>]] [--html-path] [--man-path] [--info-path]

[-p | --paginate | -P | --no-pager] [--no-replace-objects] [--bare]

[--git-dir=<path>] [--work-tree=<path>] [--namespace=<name>]

[--config-env=<name>=<envvar>] <command> [<args>]

These are common Git commands used in various situations:

start a working area (see also: git help tutorial)

clone Clone a repository into a new directory

init Create an empty Git repository or reinitialize an existing one

work on the current change (see also: git help everyday)

add Add file contents to the index

mv Move or rename a file, a directory, or a symlink

restore Restore working tree files

rm Remove files from the working tree and from the index

examine the history and state (see also: git help revisions)

bisect Use binary search to find the commit that introduced a bug

diff Show changes between commits, commit and working tree, etc

grep Print lines matching a pattern

log Show commit logs

show Show various types of objects

status Show the working tree status

grow, mark and tweak your common history

branch List, create, or delete branches

commit Record changes to the repository

merge Join two or more development histories together

rebase Reapply commits on top of another base tip

reset Reset current HEAD to the specified state

switch Switch branches

tag Create, list, delete or verify a tag object signed with GPG

collaborate (see also: git help workflows)

fetch Download objects and refs from another repository

pull Fetch from and integrate with another repository or a local branch

push Update remote refs along with associated objects

'git help -a' and 'git help -g' list available subcommands and some

concept guides. See 'git help <command>' or 'git help <concept>'

to read about a specific subcommand or concept.

See 'git help git' for an overview of the system.

If you aren’t comfortable using a terminal or CLIs, work through the lesson on the Bash Shell first.

Git is designed to protect your code but isn’t completely foolproof. Some Git commands can cause permanent data loss if used incorrectly.

The most dangerous Git commands are:

git reset --hard - discards all uncommitted changes & resets to a specific commit,git clean -f - permanently deletes all untracked files,git push --force - overwrites remote history (can cause problems for other developers),git rebase - rewrites commit history (can cause conflicts for other developers),git checkout - can discard uncommitted changes when switching branches.Most of these you will not need to use in daily work. If in doubt, copy the folder the Git repository folder so you have a local backup if needed - or better push to a remote repository before doing dangerous commands.

Remote repositories (like those on GitHub) are safe backups for Git repositories:

Your local Git repository can lose work in a few ways:

git reset --hard or git checkout,You can keep your work safe by:

git reset --hard),These practices mean that even if you do lose work locally, you’ll only ever lose a small amount of recent changes.

Git’s main function is version control of files.

Developers write code that is stored in text files. Version control gives developers a history of changes they make to text files, by providing the changes made to a given file.

Version control also allows switching between different versions of a codebase - for example switching between a version of the code that works and a version that has a bug.

Git works by keeping track of every change made to a project.

Every time a change is made and saved in Git, it is recorded in the project’s history. This means that you can go back and see exactly what changes were made when.

This keep everything approach means that anything you commit to a repository will be there forever. This is important to remember when working with secrets (like AWS keys) or with large datasets.

A local repository (repo) is created on a developer’s computer using the git init, and is contained in a folder called .git.

It contains a copy of the entire project commit history, including all the commits and branches. A local repository can be used for version control and collaboration even when working offline.

A remote repository is a copy of the local repository that is stored on a remote server, such as GitHub.

The remote allows developers to share their work.

A remote repository can be created using git remote add, and it can be connected to a local repository using git push and git pull.

The git init command is used to initialize a new repository in the current directory:

$ git init

Initialized empty Git repository in .git/

It creates a directory .git, that contains data for the new Git repository:

$ ls .git

HEAD config description hooks info objects refs

You don’t need to understand or look at these files - the most important thing to know is that the .git folder is where Git will store the entire history of your Git project:

$ tree .git

.git

├── config

├── description

├── HEAD

├── hooks

│ ├── applypatch-msg.sample

│ ├── commit-msg.sample

│ ├── fsmonitor-watchman.sample

│ ├── post-update.sample

│ ├── pre-applypatch.sample

│ ├── pre-commit.sample

│ ├── pre-merge-commit.sample

│ ├── pre-push.sample

│ ├── pre-rebase.sample

│ ├── pre-receive.sample

│ ├── prepare-commit-msg.sample

│ ├── push-to-checkout.sample

│ ├── sendemail-validate.sample

│ └── update.sample

├── info

│ └── exclude

├── objects

│ ├── info

│ └── pack

└── refs

├── heads

└── tags

The git status command allows you to check the status of your repository:

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

nothing to commit (create/copy files and use "git add" to track)

You can delete a Git repo by:

$ rm -rf .git

This can be useful when you get a Git repo into a bad state (it happens - for example if you checked in secrets) and just want to start again.

Be careful though - if you remove this folder (and you don’t have a remote copy on a service like GitHub) then you entire project history will be lost.

A repository (or repo) holds all the files and metadata associated with a codebase, including the codebase’s commit history and branches.

A repository is created using git init. A repository can be either local or remote.

Status will show you what files are staged or unstaged and tracked versus untracked.

The commit is the atomic unit of Git.

Git joins changes from multiple files into a single unit - a commit. These commits are snapshots of your project at different points in time.

A Git commit is a snapshot of an entire codebase at one point in time.

A commit has unique hash identifier - a string like d6a583a419797104d985ab8aaa471a153cd24d2f. The hash uniquely identifies a commit - i.e. the state of the entire code base at one point in time.

The difference between one commit and another is known as a diff.

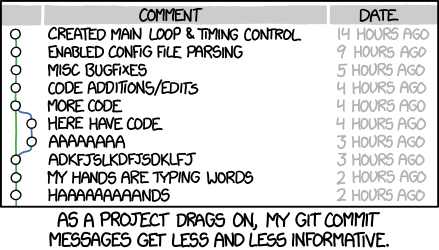

Commits are created using git commit and include a message - a short bit of text that describes what changes are made with each commit.

Let’s create a new Git repository with git init, and create a file README.md:

$ git init

$ touch README.md

If we now check what is going on, Git tells us that there is an untracked file:

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

README.md

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

We can add this file to the repository, which makes the file tracked and staged:

$ git add README.md

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: README.md

We can then commit this file, which turns the staged changes into committed changes:

[master (root-commit) 19d0f58] chore: initial commit

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 README.md

We now have this commit in our history, which we can see through git log:

$ git log --stat

commit 19d0f58e53bfcf2ee449477e60680285cd7a2d4e (HEAD -> master)

Author: Adam Green <adam.green@adgefficiency.com>

Date: Sat Aug 5 15:14:38 2023 +1200

chore: initial commit

README.md | 0

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

These changes to our Git repository live only on our local machine.

Let’s simulate some more work by changing our README.md file.

Git now tells us that we have changes to tracked files that are unstaged:

$ echo "readme changes" >> README.md

$ git status

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: README.md

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

Let’s add a new file - this file main.py is untracked by Git:

$ touch main.py

$ git status

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: README.md

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

main.py

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

We can add both of these changes into a single commit with git add ., which adds all changes in the current directory and subdirectories:

$ git add .

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

modified: README.md

new file: main.py

We now have two changes staged for commit - one change to a tracked file README.md and a new untracked file main.py.

We can create the Git commit using git commit -m 'message:

$ git commit -m 'second commit'

[master e8f9742] second commit

2 files changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 main.py

git log now shows our two commits:

$ git log --stat

commit e8f9742ab4f0c61333ce350c78cd3653bda77a9a (HEAD -> master)

Author: Adam Green <adam.green@adgefficiency.com>

Date: Sat Aug 5 15:27:56 2023 +1200

second commit

README.md | 1 +

main.py | 0

2 files changed, 1 insertion(+)

commit 19d0f58e53bfcf2ee449477e60680285cd7a2d4e

Author: Adam Green <adam.green@adgefficiency.com>

Date: Sat Aug 5 15:14:38 2023 +1200

initial commit

README.md | 0

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

There are a few ways to add files to a Git commit:

git add README.md - tracks & changes in a file README.md,git add . - tracks & changes all files in all directories,git add -u - adds changes in all tracked files (untracked files are ignored),git add * - tracks & changes all files in the current directory only.Commits are organized in a linear sequence which allows developers to see the entire history of changes made to the project. This linear sequence is the commit history.

The entire commit history is stored in the project’s repository and can be viewed using git log.

The git log command displays a list of all the commits made to the repository.

Each entry shown by git log includes the commit’s SHA-1 checksum, the author’s name and email, the date and time of the commit, and the commit message.

$ git log

commit 8a121f9375c5e33277d34810a674410c94588b8d (HEAD -> master)

Author: Your Name <your-email@example.com>

Date: Mon May 30 23:12:39 2023 +0000

Initial commit

Two useful git log commands are:

git log --pretty=fuller --abbrev-commit --stat -n 5,git log --pretty=fuller --abbrev-commit --stat -n 5,Conventional Commits is a standardized format for writing commit messages that makes project history easier to read and automate.

The format follows this pattern:

<type>: <description>

[optional body]

[optional footer(s)]Common types include:

Examples:

$ git commit -m "feat: add user authentication"

$ git commit -m "fix: resolve login button styling issue"

$ git commit -m "docs: update API documentation"

$ git commit -m "chore: update dependencies"

Using conventional commits provides:

Many teams and open source projects use conventional commits to maintain clean, professional commit histories.

GitHub is a web-based platform that hosts Git repositories and adds collaboration features on top of Git.

Git is the version control system that tracks changes in your code. GitHub is a service that hosts Git repositories and makes it easier to collaborate with others.

GitHub is as a central hub where developers can share their code, contribute to others’ projects, and collaborate on software development.

Github is not the only platform that developers use to work with Git repositories - services like Azure Devops or Gitlab offer similar functionality to Github.

So far we have only created a Git repository locally - it only exists on our local machine.

To put a Git repo onto Github, we need to do a few things:

After logging in to Github, you’ll find a '+' button on the upper right side where you can add a new repository.

You’ll be directed to a new page where you’ll be asked to fill out some information:

Repository Name: Choose a name for your GitHub repository. It should ideally match your local repository to avoid confusion.

Description (optional): You can provide a short description of your project.

Visibility: Choose whether the repository should be public (visible to everyone) or private (only visible to you and collaborators you choose).

Initialize this repository with: This section should typically be left blank as you're pushing an existing repository.Almost always it’s best to initialize empty repositories on GitHub.

Next, you need to link your local repository to the remote repository on GitHub and push your commits to it. To do this, use the following commands:

Now you have a repository on GitHub, you can push your local repo up into GitHub by adding it as a remote repository called origin:

$ git remote add origin https://github.com/USER/the-repo-name

$ git push -u origin master

git push -u origin master pushes your commits to the ‘master’ branch of the ‘origin’ repository. The -u flag tells Git to remember the parameters.

Now your local Git repository is connected & backed up to your GitHub repository, enabling version control.

Other developers can now clone and work on it separately, enabling collaboration.

A branch is a copy of the codebase that can be worked on independently.

Branches allow you to work on multiple features or bug fixes in parallel without affecting the main development branch.

A branch is given a human readable name like amazing-new-feature or fix-the-bug.

A branch is created using the git branch command and can be switched between using the git checkout command.

When a branch is created, it is based on the current state of the codebase, and it includes all the commits up to that point.

Any new commits made while on that branch will be added to that branch, creating a separate branch history.

Once the work on a branch is finished, it can be merged back into the main codebase using git push, git pull or git merge. This allows developers to incorporate their work into any other branch.

The ability to work on multiple branches allows developers to work on features or bug fixes in separate versions of the same codebase, without affecting other branches of the codebase.

Similar to commit messages, consistency around branch naming can be useful.

For example, prefixing with feature/, fix/, or a GitHub issue number can help other understand what a branch is used for.

By default Git starts on the master branch.

For Git the master branch is the default branch - it’s the one that is automatically created when you create a Git repository:

$ git status

On branch master

nothing to commit, working tree clean

It’s also common for the default branch to be called main.

We can create a new branch using git branch:

$ git branch tech/requirements

We can then switch to this branch with git checkout:

$ git checkout tech/requirements

Switched to branch 'tech/requirements'

This new branch is at the same state as master.

We can add commits to a branch using our git add and git commit workflow:

$ echo "pandas" >> requirements.txt

$ git add .

$ git commit -m 'added Python pip requirements'

[tech/requirements 9a963bf] added Python pip requirements

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 requirements.txt

We now have two branches master and tech/requirements.

We can look at the difference between these branches using git diff:

$ git diff master tech/requirements

diff --git a/requirements.txt b/requirements.txt

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..fb6c7ed

--- /dev/null

+++ b/requirements.txt

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

+pandas

Diffs can be quite large – many developers will view the diff between branches on a tool like GitHub or using git difftool.

We can bring our changes from tech/requirements into our master branch using git pull:

$ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

$ git pull . tech/requirements

From .

* branch tech/requirements -> FETCH_HEAD

Updating e8f9742..9a963bf

Fast-forward

requirements.txt | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 requirements.txt

git pull allows specifying the repository (in the command above .).

It’s also possible to use git merge:

$ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

$ git merge tech/requirements

Updating e8f9742..9a963bf

Fast-forward

requirements.txt | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 requirements.txt

Currently we have our two branches locally – we can push these branches up to our remote repository origin on GitHub:

$ git push origin master

Enumerating objects: 9, done.

Counting objects: 100% (9/9), done.

Delta compression using up to 8 threads

Compressing objects: 100% (5/5), done.

Writing objects: 100% (9/9), 727 bytes | 727.00 KiB/s, done.

Total 9 (delta 1), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (1/1), done.

To github.com:ADGEfficiency/the-repo-name.git

* [new branch] master -> master

branch 'master' set up to track 'origin/master'.

$ git push origin tech/requirements

Total 0 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0

remote:

remote: Create a pull request for 'tech/requirements' on GitHub by visiting:

remote: https://github.com/ADGEfficiency/the-repo-name/pull/new/tech/requirements

remote:

To github.com:ADGEfficiency/the-repo-name.git

* [new branch] tech/requirements -> tech/requirements

Even experienced developers make mistakes with Git. Knowing how to fix common issues will save you time and frustration.

Merge conflicts happen when Git can’t automatically merge changes because two branches have edited the same lines of code.

When this happens, Git will mark the conflicts in your files:

<<<<<<< HEAD

This is the change in your current branch

=======

This is the change in the branch you're merging

>>>>>>> branch-nameTo resolve a merge conflict:

git addgit commit$ git merge feature/login

Auto-merging user.py

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in user.py

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

# After resolving conflicts in your editor

$ git add user.py

$ git commit

When Git encounters a merge conflict, it modifies the affected files by inserting special conflict markers to show you exactly where and what the conflicts are. Let’s break down these markers in detail:

<<<<<<< HEAD

This is the change in your current branch

=======

This is the change in the branch you're merging

>>>>>>> branch-nameThese markers divide the conflicting section into distinct parts:

<<<<<<< HEAD======= separator represents the content from your current branch (the branch you were on when you started the merge)HEAD refers to the latest commit on your current branch=======>>>>>>> branch-name======= separator and this marker represents the content from the incoming branch (the branch you’re trying to merge in)branch-name will be replaced with the actual name or commit reference of the branch you’re mergingWhen Git shows you these markers, it’s essentially saying:

=======)”=======)”Git cannot automatically decide which version to keep, so it’s asking you to make that decision.

Conflicts typically occur when:

Let’s say you’re working on a feature branch called feature/login and you have this function in your current branch:

def authenticate_user(username, password):

if username == "admin" and password == "secret":

return True

return FalseMeanwhile, your colleague has changed the same function in the main branch to use a database check:

def authenticate_user(username, password):

return database.check_credentials(username, password)When you try to merge main into your feature branch, Git will create a conflict that looks like:

def authenticate_user(username, password):

<<<<<<< HEAD

if username == "admin" and password == "secret":

return True

return False

=======

return database.check_credentials(username, password)

>>>>>>> mainTo resolve this conflict, you need to:

For example, you might decide to keep the database authentication but add your admin check as a fallback:

def authenticate_user(username, password):

# Try database first

if database.check_credentials(username, password):

return True

# Fallback for admin during development

if username == "admin" and password == "secret":

return True

return FalseAfter editing, you would:

git add authenticate.py

git commitGit will automatically generate a merge commit message explaining that you resolved conflicts.

A single file can have multiple conflict sections, each wrapped in its own set of conflict markers. You need to resolve each one individually.

Most modern IDEs and code editors have built-in support for resolving merge conflicts with a visual interface that makes it easier to choose between “yours” (HEAD), “theirs” (incoming branch), or combine the changes.

Understanding these conflict markers is essential for effective collaboration with Git, as merge conflicts are a normal part of the collaborative development process.

Git gives you multiple ways to undo changes, depending on what you need:

Use git reset --soft to undo a commit but keep all changes staged for a new commit:

$ git reset --soft HEAD~1

This is useful when you committed too early or need to change your commit message.

Use git reset (or git reset --mixed) to undo a commit and keep changes unstaged:

$ git reset HEAD~1

This gives you a chance to re-stage only some changes for your next commit.

Use git reset --hard to completely remove a commit and all its changes:

$ git reset --hard HEAD~1

Warning: This permanently discards changes, so be careful!

If you need a specific file from another branch without switching branches:

$ git checkout branch-name -- path/to/file

This brings the file from the specified branch into your current branch.

When you need to switch branches but aren’t ready to commit:

# Save your changes

$ git stash

# Switch branches, do other work

$ git checkout another-branch

# Come back and restore your changes

$ git checkout original-branch

$ git stash pop

If you forgot to add a file or need to fix your commit message:

# Add any missed files

$ git add forgotten-file.py

# Amend the commit

$ git commit --amend

If you accidentally deleted a commit with reset --hard, you can usually recover it:

# Find the lost commit SHA

$ git reflog

# Recover the commit

$ git checkout <commit-sha>

$ git checkout -b recovery-branch

$ cp -r my-repo my-repo-backup

When in doubt, use git status to see where you are

For dangerous operations, try them on a new branch first

Remember that pushed commits are harder to rewrite - be extra careful with git push --force

Use descriptive commit messages - they’ll help you identify what went wrong later

The learning curve with Git can be steep, but the more you use it, the more comfortable you’ll become with fixing mistakes when they happen.